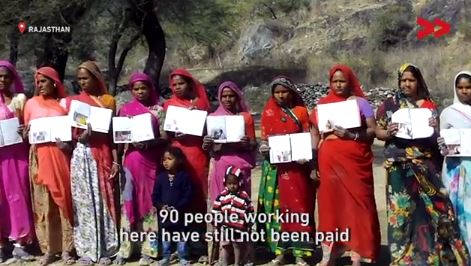

90 workers waited for MNREGA payments totalling more than 3.5 lakh for over three months. The wait ended when Shambhulal Khatik made a video documenting the problem and holding the authorities accountable.

In a small village in the southern part of Rajasthan, Chain Singh was waiting for his payment under the government’s rural employment scheme. Singh and a group of workers were working on the construction of toilets in the village of Delwara under the government’s MNREGA scheme. With the delay in payment, the workers had to stall the construction as they didn’t have any money to buy construction material and were not being paid. It was becoming difficult to run their households. “If we aren’t paid, what will we eat?” he asks.

Video brings impact in less than a week

MNREGA or the Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Act (2005) is one of the government’s flagship social safety nets. It guarantees 100 days of paid work to at least one member of each rural household and the work is aimed at the creation of public infrastructure.

Hailed as the world’s largest public works programme, MNREGA has 182 million beneficiaries on its rolls, according to figures from 2014. But lack of work, delayed payments, exaggerated impact figures and misappropriation of funds plague the scheme in many states.

In Delwara, 90 workers did not receive their payment for over three months; under the Act, complete payment is to be made within 15 days of completion of the work failing which the government must compensate the workers for the delay. The rate of compensation is fixed at 0.05% of the unpaid wages per day and even this meagre amount does not make it to the workers in many cases.

[caption id="attachment_15369" align="aligncenter" width="471"] Despite having the right documents, the workers did not receive timely payment.[/caption]

Despite having the right documents, the workers did not receive timely payment.[/caption]

When Community Correspondent Shambhulal Khatik got a whiff of the problem, he approached the village-level overseer of the scheme (rozgar sahayak) and learnt that the total amount due to the 90 workers was over 3.5 lakh. The 90 workers had valid job cards with photographs and bank accounts, and all their names were on the muster rolls as well. “We spoke to the village head, he said that he has met the authorities but the money is not being released by the higher authorities”, says Singh.

Shambhulal believes that the presence of the camera made the impact possible.

Shambhulal made a video documenting the problem, and along with the workers, decided to write an application to the higher authority. But they did not even need to submit the application; the Panchayat, a key body in the implementation of the scheme, made the payment within five days. Shambhulal believes that the presence of the camera made this possible. “I went to the Panchayat with my camera in hand and demanded an answer, the process of reporting itself became an important step in solving the problem”, he says.

However, Shambhulal is still wondering why the payments were delayed. The Samiti did not provide an explanation for the delay. It could be corruption, bureaucracy or problems of computerised data, and he wishes he knew which it was, because unless the community understands the workings of the higher authorities, it is quite likely that the problem could repeat itself. For Shambulal, these are subjects for future reporting. In the meantime, he is glad to have achieved this concrete impact.

[caption id="attachment_15368" align="aligncenter" width="471"] Shambhulal believes that community media is a powerful tool.[/caption]

Shambhulal believes that community media is a powerful tool.[/caption]

Scheme rife with problems of implementation

While the story of Delwara is one of success, such stories are often the exception and not the norm. The workers had not been paid since February. Shambhulal reported the issue in April and the payment came through in April itself. In June, the problem was back, and no one knew what was causing the delay. The workers from the village once again found themselves waiting for their payment for May and this time, the money came through only in the last week of July. Though a delay of three months may not sound like a lot, it can make a huge difference for someone living hand to mouth.

According to the official MNREGA figures, Delwara has 1,425 workers who have sought job cards, but only a little more than third of them have been issued job cards. Worse still, only 221 workers are eligible for payment as of now. This means that another 359 people have job cards but cannot be paid even if they do the work, because of various technical considerations. For instance, their photo may not be updated; their bank account may not be linked; they may not have an Aadhar. These 359 workers will be doing the work expecting to be paid, and then will get a rude shock when they are told various technicalities are preventing them from being paid.

Delay in MNREGA payments is common and in Rajasthan, the pending amount totalled nearly 2000 lakh in 2015-16. Rajasthan is reported to lead in the creation of jobs under MNREGA with 2.4 crore jobs and has a relatively high percentage of timely payments. Singh and his fellow workers, however, do not fit into this picture of a state setting an example. They did not receive any compensation for the delay either. The system of compensation has its own loopholes; workers are not compensated for each day’s delay in payment. The compensation is calculated only till the date a demand for payment is raised at the district level. There is not only a delay in the payment of wages but also in the payment of compensation for the delay. According to the Ministry of Rural Development, the delays occur at the state level.

Moving to a cashless transaction scheme is only giving rise to problems when 1.2 crore workers are reported to not have bank accounts.

Here’s what the Ministry is doing to fix the problem- turning to technology. The Ministry is moving all operations to the online MIS (Management Information System) to ensure transparency but on ground, the move is only alienating workers. Any discrepancy in the records online leads to non-payment of wages and delays. Invalid and mismatching account numbers, errors in uploading data, arbitrary deletion of workers’ names from muster rolls and closure of schemes without immediate intimation are some of the discrepancies. Linking MNREGA accounts to Aadhar is only believed to make matters worse. Moving to a cashless transaction scheme is only giving rise to problems when 1.29 crore workers are reported to not have bank accounts in one state alone.

While workers wait for their payment, Panchayats and Samitis misuse the free hand that they have at the local level. It is also easy for local authorities to wash their hands of all responsibility and cast the blame on technology. The former was a problem in Delwara too until some years ago, Shambhulal says that workers were sometimes paid in kind. They were given sacks of grain instead of account transfers despite having bank or post office accounts. “Earlier, when the workers did receive payment, many a time, the Panchayat would appropriate one-fifth of the money”, says Shambhulal. On one hand, payment is not made on time, and on the other, the Panchayat threatens to cut off the ration supply if the project is not completed on time, says Singh. In such cases, the workers are left with their hands tied.

The scheme is touted as the largest of its kind in the world but at the ground level, people like Singh wait endlessly for the benefits that they are entitled to. Shambhulal’s video ensured that the workers in Delwara got their payment at the earliest, similar efforts have been made by our correspondents in other states so that rural communities are able to claim their rights.

Article by Alankrita Anand

Commemorating soldiers of The Indian National Army in Betul

In this video, our community correspondent Mohanlal Sheelu is participating in a program commemorating the ex-soldiers of INA. From the Ghoradongri block of Betul District, Madhya Pradesh, around 200 people had joined the Indian National Army.

Highlights from the Video Volunteers Annual Report 2021-2022

In the year 2021-2022, Video Volunteers reached a huge number of people. Each video, on average, documented a problem, a ground reality that affected nearly 35,000 people. And we reported more than 1500 stories last year. Impacts achieved by our community correspondent have benefited 3.2 million people, in total.