The people living on the banks of the Kelo Dam are risking their lives to go to school and find work.

Imagine sending your child to school wading and swimming through several feet of water. This is the reality across the villages on banks of the Kelo river in Chhatisgarh. A dam was constructed on the river in 2014. The reservoir has started flooding the roads, particularly after monsoons. “I’m really scared for the smaller children. They could get into serious trouble: the road is completely flooded and even the sides are water logged. The school, too, is very close to the water,” says Pallavi, a teacher at the local middle school at Gerwani.

The Dilip Singh Judeo Irrigation Project (DSJIP) on the Kelo river was constructed at the cost of Rs 600 crores. The state government declared that it will irrigate 23,000 hectares of farming land. Despite studies repeatedly showing that the costs often outweigh the benefits, the race for constructing dams in India continues unabated. In 1947, India had only 300 dams. Today that number is over 5000 according to the International Commission of Large Dams.

In 1958, speaking to those displaced by the Hirakud Dam, the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said, “If you are to suffer, you should suffer in the interest of the country.” Almost 50 years later, the Supreme Court echoed this in a judgement in favour of the Sardar Sarovar Project when it deemed that the cost--displacing 70,000 people a majority of whom were from the Scheduled Tribes--outweighed the benefits. This has been the mainstay of the government’s argument in favour of dams, even though comprehensive cost to benefit assessments are thin on the ground. Those displaced and disadvantaged should just learn to bear the brunt of ‘development’ in the name of greater good.

The villages bordering the DSJIP in the Raigarh district of Chhatisgarh, inhabited by indigenous people, are yet again being treated as footnotes in the glorious narrative of development. In Chinhouna, one of these villages, the traditional occupation consists of weaving hand-crafted bamboo mats. But thanks to the dam reservoir, they have limited access to the markets. Those who can afford it, use precarious rafts loosely strung together on inflated rubber tubes to cross the lake.

[caption id="attachment_15271" align="aligncenter" width="360"] People are forced to use makeshift rafts made with inflated rubber tubes to cross the Kelo dam.[/caption]

People are forced to use makeshift rafts made with inflated rubber tubes to cross the Kelo dam.[/caption]

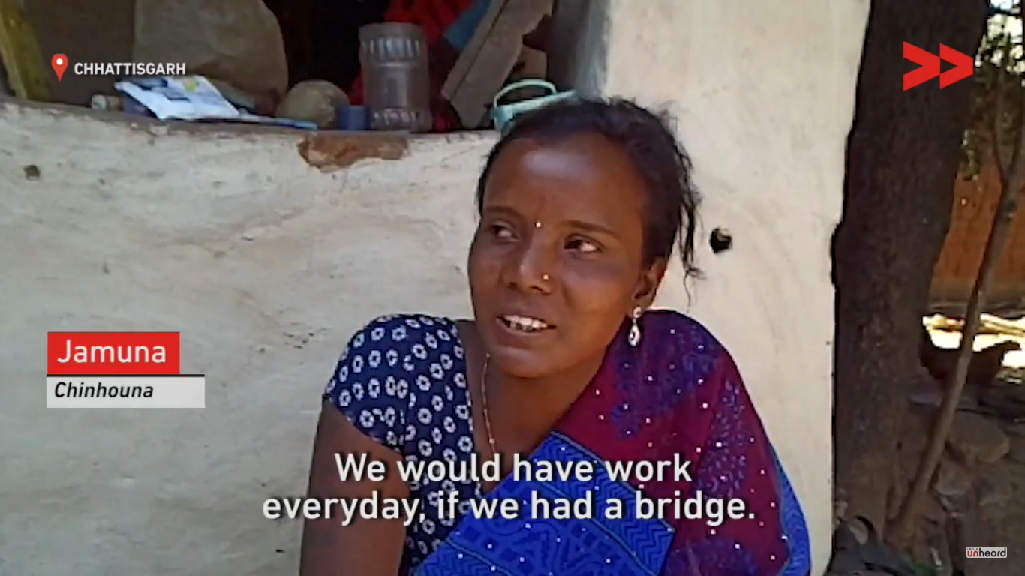

Kamla, a resident of the village adds, “We are troubled by the dam--we can’t even go to look for daily wage labour.” Her neighbour Jamuna chimes in, “We could find work everyday if we had a bridge.”

[caption id="attachment_15272" align="aligncenter" width="1025"] “We could find work everyday if we had a bridge.”[/caption]

“We could find work everyday if we had a bridge.”[/caption]

Community Correspondent Rajesh Gupta has helped the community and the deputy head of the panchayat meet the District Collector. “We have had three meetings with the Collector and one with the in-charge of the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (Prime Minister’s Scheme for Village Roads). But as yet no steps have been taken.” The only road they have remains submerged under five to ten feet of water through the year. Meanwhile, children and adults continue to risk their lives as they go about their daily lives.

[caption id="attachment_15273" align="aligncenter" width="995"] Children going to school, located across the dam.[/caption]

Children going to school, located across the dam.[/caption]

Research points out that marginalised communities always bear the brunt of dammed development--indigenous people (Scheduled Tribes) form about 8% of the total population but 47% of those displaced by such projects. While the government’s main rationale for dams remain bringing more arable land under irrigation, farmers across the country continue to suffer from droughts, crop failure, falling prices and burden of loans leading to the highest numbers of farmers’ suicides anywhere in the world. Construction of ever higher dams continue despite the high human and environmental costs and limited and questionable benefits. Historically disadvantaged groups continue to be pushed to the margins of the developmental discourse of the country. It is time we started asking critical questions--development for whom? Can we condemn a child to face the daily risk of death by drowning on her way to school for the ‘greater good’?

This article, written by Madhura Chakraborty, is co-published with FirstPost.

Displaced locals request for rehabilitation and compensation

The dam at Kothida, Bharud Pura, Dhar district, Madhya Pradesh took just a year to get a crack. More than 11 surrounding villages are at risk now due to this leakage and residents are asked to vacate the area.

Livelihood at stake in Chatra

The matter is serious - in Jatrahi village under Sikid village council of Chatra Block, Chatra District of Jharkhand, 25 families of Bhuyan community were living for 70 years and they are asked to relocate.